By Dr Rita Pemberton

Like elsewhere in the Caribbean, the enslaved population of Tobago eagerly looked forward to emancipation on August 1, 1838, because they expected they would be able to adjust their lives in the direction they desired.

Their aim was to create a space for themselves and establish independent means of employment to provide for their families an existence that was free of plantation control. They were disappointed on both counts. The framers of the emancipation law made no provision for the allocation of the island’s land resources to the freed men and women. The planting and merchant fraternity, as landowners and members of the assembly and council who were empowered to institute laws, remained in full control of the island’s resources and implemented laws intended to prevent land ownership by the newly freed population.

Secondly, emancipation notwithstanding, it was certainly not the intention of either the imperial or colonial authorities to cause the demise of the sugar industry because of a dearth of labor. In addition, there were no other employment opportunities on the island. Hence the freed Africans found themselves still under planter control both for access to land and for employment. This was made very evident immediately after August 1, when the planters expected the freed population to return to work as usual, but they, in defiance, refused to do so under the terms being offered.

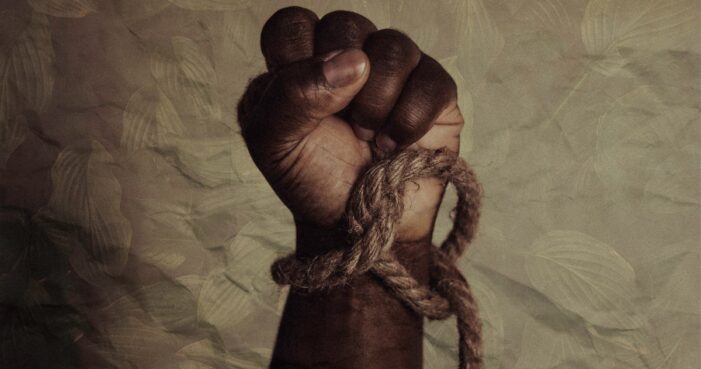

The first hurdle which faced the free population was the need to circumvent the restrictive presence of the ruling planter class and its allies. Enslavement was enforced by two sets of chains. The physical chains included brutal punishments., enforced working hours, abuse and sales.

After emancipation, restrictive laws and prison replaced the whip of enslavement, but the freed Africans resisted planter control. The first years of freedom were marked by planter/worker conflicts over wages, hours of work and terms of employment.

The freed population was able to take advantage of the weakened planter position, which was caused by the decline of the sugar industry and their failure to obtain imperial support for their requests to be allowed to import immigrant labor. The planters were forced into dependence on the resident workers, who in turn were able to wring out an advantage for themselves in terms of access to land and opportunities to purchase or rent portions of unused estate land from cash-strapped planters. While planters saw potential advantage from this strategy, which would provide a resident labor force whose services would be readily available, to the freed Africans, it was a means to an end. By securing multiple labor arrangements, they were able to reduce planter control, increase their earnings and reduce dependence on the planters.

In fact, even though wages were not increased, the workers benefited from the multiple employment and their ability to supplement their incomes from their gardens. The tables turned and planters became dependent on labor.

Overcoming the second hurdle was a much more challenging exercise, because it was not readily recognizable for what it was and could not be overcome by a single act. Under cover of the pretense of a civilizing mission, psychological chains which exploited the notion of inferiority and subhuman nature of African people constituted the tentacles of colonialism. This led to self-hate. Africans were black and ugly, and all negatives were associated with their blackness. The traditions of Africans were savage and pagan, while the corollary was that white was superior, more intelligent, civilized and pretty.

The plantation system was ordered to afford privilege by color. Some mixed-race men were allowed to hold positions because of the small white population on the island. Within the community of the enslaved, the browns were elevated over the blacks. This created the desire for “whiteness” as a means of social improvement, which is reflected in the class system, as are notions of development, which invariably meant motion away from things African. So the class system was reflected in housing, dress and foods.

In addition to the forced separation from their homeland, there was the separation from their history. The fallacy of Africa as “the dark continent” with no history found fertile ground in Europe. Enslaved Africans were led to believe that the falsehood that the history of Africans, which was said to have begun in captivity and enslavement, was something to be ashamed of. For generations, historical knowledge of the great African civilizations was kept secret from the descendants of enslaved Africans, who were made to study European history and history written by Europeans. Self-hate has persisted down to the present day. It is reflected in the effort some people make to alter themselves and to be something other than ourselves. Hence skin-lightening creams, body-changing mechanisms and beauty regimes reflect people who are not comfortable in their own skins. Some parents still express a preference for the “light-skinned” children and those with “nice” hair, to the detriment of the self-image of their darker offspring.

In order to feel acceptable, some people accept the superficial items that are advertised or projected in the media, as they feel the need to look like those people who are in control. In this way too, importance is attached to the possession of brand-name items and /or the dress of movie stars and entertainers. Huge industries, which feed the coffers of overseas investors, have been established.

Europeanisation has been equated with modernity and valuable traditions have been sacrificed in the process. The Tobago coconut industry was killed when coconut oil was labelled a cause of heart disease and Tobago food was classified as “poor man food,” stimulating the growth of the fast-food industry on the island, despite its impact on the health of the population. Coconut oil and ground provisions became “gentrified” when industries which generated income outside the region were established.

After 184 years of emancipation, the negatives of coloniality remain evident in the society. More effort is required to break the psychological chains of enslavement, and it must start with self-love.

This commentary was originally published in the Trinidad & Tobago Newsday publication. Dr. Rita Pemberton is a former Senior Lecturer in History at UWI, St. Augustine. She holds a PhD from UWI and has taught the History of Trinidad and Tobago, Imperialism, and various aspects of Caribbean History at UWI St. Augustine from 1990- 2013. She is a former Head of the Department of History and Deputy Dean, Student Affairs in the Faculty of Humanities and Education and a past President of the Association of Caribbean Historians.